Introduction

The purpose of this short post is to give an analogy with other, more familiar, objects and operations that have the same properties than pairings. Even though this won’t explain the intuition behind the definition of pairings in elliptic curves, having such an analogy and mental model may help to understand its use cases and its limitations.

Recap

Let’s quickly recap what an elliptic curve point is. One way to define an elliptic curve over a field $\mathbb{F}$ is as the set of pairs $(x,y)$ of elements of $\mathbb{F}$ such that $y^2 = x^3 + ax + b$. Here $a$ and $b$ are fixed and are part of the definition of the elliptic curve. For example, the curve Secp256k1 used for digital signatures in Bitcoin and Ethereum is the set of solutions $(x, y)$ to the equation $y^2 = x^3 + 7$, with $x$ and $y$ being elements of $\mathbb{F}_p$ for a particular 256-bit long prime.

So, a point $P$ on an elliptic curve is just a pair $P = (x,y)$. There is a rule of addition that takes two elliptic curve points and returns a new one again on the same curve. This rule of addition is not the coordinate-wise addition. That is, if $P=(x,y)$ and $Q=(x’, y’)$ are two points of the same elliptic curve, then their addition is not the point $(x+x’, y+y’)$. I mean, one can certainly define and compute such thing. And in fact, that is very useful in other contexts. But that won’t be a point in the curve. That is, it won’t satisfy $(y+y’)^2 = (x+x’)^3 + a(x+x’) + b$. The rule of addition that’s referred to when talking about elliptic curves is another one. There are multiple online resources (Moonmath, Pairings for beginners) that go through it with nice pictures and intuitions. For the scope of this post, it doesn’t really matter the actual definition. Let’s just use it and denote it by $P \oplus Q$ to distinguish it from the element-wise addition $(x, y) + (x’, y’) = (x+x’, y+y’)$ of $\mathbb{F}^2$.

In the context of zk-SNARKS, points on elliptic curves are used as a tool to commit to values. In the interactions between the prover and the verifier, the verifier usually makes tricky challenges for the prover to test him. This kind of challenge involves asking for values that must be consistent with previously received values in some arithmetic sense. For example, suppose there is a set of public parameters that contain the points $T = \tau G_1$ and $T’ = \tau G_2$. Both parties know them but neither party knows the actual value of $\tau$. Further, assume the prover has already sent the point $aG_1$ to the verifier. Then, as part of the protocol, the verifier chooses a random field element $z$, sends it to the prover, and expects to receive as a response a value $y$ along with another point $bG_1$ such that $a - y = b (\tau - z)$. But this last equality is hard to check for the verifier because he doesn’t have access to $a$, $b$, or $\tau$.

Over the cartesian plane

Let’s switch to another setting with more familiar tools than the realm of elliptic curves. Instead of working over an elliptic curve let’s work over the real cartesian plane \(\mathbb{R}^2 = \{(x,y): x, y \in \mathbb{R}\}\)

That is, points can be any pair with real coordinates. The generators, instead of being points $G_1$ and $G_2$ in the elliptic curve, are vector $v=(v_1, v_2)$ and $w=(w_1, w_2)$ in $\mathbb{R}^2$. All operations will be component-wise. Let’s bring the same stuff we had before. There are public parameters that contain the vectors $\tau v = (\tau v_1, \tau v_2)$ and $\tau w = (\tau w_1, \tau w_2)$. Both parties know $\tau v$ and $\tau w$, but neither party knows the value of $\tau$. That’s silly to assume because $\tau$ can be computed for example as the first coordinate of $\tau v$ divided by the first coordinate of $v$ (both values are known to all parties). But let’s assume for the sake of the example that we live in a world where that’s not possible. Either because it’s too computationally intensive or because the division of real numbers has not been discovered yet.

Now the prover holds a real value $a$ and uses it to compute the vector $av = (av_1, av_2)$ and sends it to the verifier. The verifier responds with some random real number $z$ and expects the prover to reply with a real number $y$ along with a vector $bv$ such that $a - y = (\tau - z) b$. As before, this cannot be computed directly.

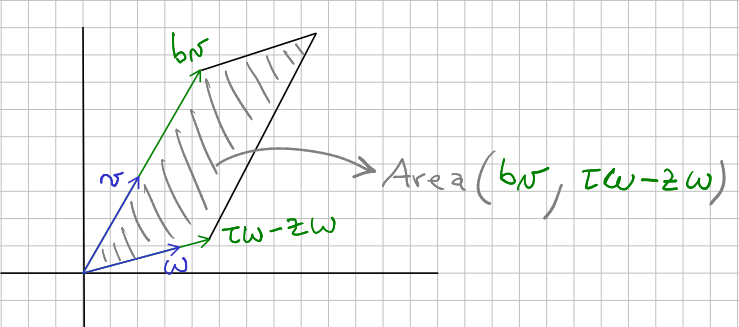

But in this setting, there is a natural workaround. The verifier can use geometric tools and, for instance, compute areas. Say the verifier goes for it and computes the area of the parallelogram with sides $bv$ and $(\tau w - z w)$.

If you work out the math you’ll find that that area is equal to \(\text{Area}(bv, \tau w - zw) = (\tau - z)\cdot b\cdot \text{Area}(v, w)\)

On the other hand, the verifier can compute the area of the parallelogram with sides $av - yv$ and $w$. That results in \(\text{Area}(av - yv, w) = (a-y)\cdot\text{Area}(v,w)\)

So, as long as $\text{Area}(v, w)$ is not zero, we get that the equality $a - y = (\tau - z) b$ holds if and only if the equality $\text{Area}(av - yv, w) = \text{Area}(\tau v - zv, bw)$ holds. And this last equality depends only on elements known to the verifier! (Recall that the (signed) area is computed as $\text{Area}((u_1, u_2), (u_1’, u_2’))) = u_1u_2’ - u_2u_1’$).

The key is the bilinearity!

Note that the above approach was possible thanks to two properties of areas of parallelogram:

- First, those areas can be efficiently computed. Even in our imaginary world where divisions of real numbers are inefficient.

- Second, that $\text{Area}(\alpha v, \beta w) = \alpha\cdot\beta\cdot\text{Area}(v, w)$ for all $\alpha, \beta \in \mathbb{R}$. This is a consequence of the bilinearity of the $\text{Area}$ function.

With this in mind, the question naturally arises: are there bilinear functions like $\text{Area}$ with the above properties in the setting of elliptic curves over finite fields? If so, we could carry this approach to the elliptic curve setting and we are done. So what do we mean by this? We ask for the existence of a function, let’s denote it $\text{A}$, that takes two elliptic curve points and returns a field element in $\mathbb{F}_r$ such that

- $\text{A}(P, Q)$ can be computed efficiently.

- $\text{A}(a P, b Q) = a \cdot b \cdot \text{A}(P, Q)$ for all $a, b \in \mathbb{F}_r$.

Well, the answer is … no, there isn’t. At least not that the scientific community is aware of. That’s because if such a function exists, then one can solve the discrete log problem for the elliptic curves. And that’s because we are not in the imaginary world where division is not possible. Precisely, if such a function $\mathbb{A}$ exists, then $a = \text{A}(a P, Q) / \text{A}(P, Q)$. So we recover $a$ from $aP$ and any other point $Q$ such that $\text{A}(P, Q) \neq 0$.

Tweaking a bit the cartesian plane example

We are going to tweak the approach in the Cartesian plane. We are doing so just to obtain something similar in spirit to what can be carried away to the elliptic curve setting.

The whole point in the cartesian plane was that checking the equality $a - y = (\tau - z) b$ is equivalent to checking the equality $\text{Area}(av - yv, w) = \text{Area}(\tau v - zv, bw)$. But it is also true that $\text{Area}(av - yv, w) = \text{Area}(\tau v - zv, bw)$ if and only if $2^{\text{Area}(av - yv, w)} = 2^{\text{Area}(\tau v - zv, bw)}$, since $2^x$ is an injective function.

What’s the point of doing that? You may ask. The answer is none. None for the purposes of solving the problem in the cartesian plane in our imaginary world without divisions. The only point is illustrative since pairings in elliptic curves are functions that are more resemblant to $2^{\text{Area}}$ than they are to just the function $\text{Area}$. Let’s call it $\text{ExpArea}$. That is, $\text{ExpArea}(v,w) = 2^{\text{Area}(v,w)}$. Let’s see what happens to the bilinearity:

\[\text{ExpArea}(\alpha v, \beta w) = 2^{\text{Area}(\alpha v, \beta w)} = 2^{\alpha \cdot \beta \text{Area}(v, w)} = \text{ExpArea}(v,w)^{\alpha \cdot \beta}\]In summary, this function has two properties:

- $\text{ExpArea}$ can be computed efficiently.

- $\text{ExpArea}(\alpha v, \beta w) = \text{ExpArea}(v,w)^{\alpha \cdot \beta}$ for all $\alpha, \beta \in \mathbb{R}$.

And just as before, any function with those properties can be used as a proxy to the check $a - y = (\tau - z) b$ using only data the verifier has.

Pairings, finally!

What exists are functions $e$, called pairings, such that

- $e(P, Q)$ can be computed efficiently.

- $e(a P, b Q) = e(P, Q)^{a\cdot b}$ for all $a, b \in \mathbb{F}_r$.

And so, during the protocol, when the verifier holds the elements $aG_1, bG_1$, $z$, $y$ and wants to check whether $a - y$ equals $b(\tau - z)$, then he can instead check that $e(aG_1 - yG_1, G_2)$ equals $e(bG_1, \tau G_2 - zG_2)$. Recall that $G_1$, $G_2$ and $\tau G_2$ are part of the public parameters of the protocol.

There isn’t just a single pairing function. There are many. There’s the Weil pairing, the Tate pairing, the Ate pairing, etc. Even optimizations may introduce slightly different versions of a pairing. For example, there are cases where there’s a shortcut to compute $e(P, Q)^3$ that’s faster to compute than $e(P, Q)$. And that’s fine since it’s still a bilinear function.

Don’t pairings weaken ECC? By reducing DLOG over EC to DLOG over finite fields?

We’ve sketched an idea of why a function $e$ such that $e(aP, bQ) = a\cdot b\cdot e(P, Q)$ doesn’t exist. And that’s because the discrete logarithm over elliptic curves would be easy to crack. More precisely, to find $a$ from $aP$, and $P$ just find some $Q$ such that $e(P, Q)$ is nonzero and then $a = e(aP, Q) / e(P, Q)$.

But on the other hand, pairings have a similar property, namely $e(aP, Q) = e(P, Q)^a$. So this suggests a way to reduce discrete logarithms over elliptic curves to discrete logarithms over finite fields! This looks bad since over finite fields there are many more tools to crack it than over elliptic curves. There’s an attack based on this fact called the MOV attack. It isn’t as bad as it sounds. And that’s because we’ve swiped a lot of details under the rug. For example, the value $e(P, Q)$ lives usually over an extension of the original field $\mathbb{F}_r$. Discrete log attacks over these extensions are less effective.

So, don’t panic kids, the MOV attack is not under the bed… at least for now.