Introduction

GPUs can handle many simultaneous calculations. They have three main applications:

- Data-intensive computations.

- Complex algebraic operations.

- Image or signal processing.

The third one, of course, is the original purpose for GPUs.

How do GPUs parallelize? In this article, we’ll focus on CUDA, Nvidia’s architecture for GPU computing. GPUs parallelize by splitting our program’s computation between threads. The GPU will run these threads concurrently and process as many in parallel as it can.

There are many architecture-specific features to help us, too.

- How threads are grouped in blocks and warps, and how they interact.

- The use of different memory types.

- Consecutive memory access operations.

- Locks and atomic operations.

All this power, however, does not come without its share of responsibility. There are several factors to consider when programming for GPUs.

- The GPU and CPU have separate memory spaces.

- One cannot access the other’s memory.

- Copying data from one to the other is very expensive.

- Memory accessing is not trivial.

- GPU algorithms shine when memory access is consecutive, and coalesced.

- The application of memory optimizations usually depends on consecutive access.

Now, the sudden rise in practical applications for cryptography theory concepts in recent years caused some to research and develop specialized hardware. As of the writing of this article, the research of zero-knowledge and cryptography hardware resulted in and is focused on FPGAs and ASICs.

Case Study

In order to see these concepts at work, we showcase the parallelization of an algorithm used in a state-of-the-art zero-knowledge prover.

- We explain its sequential version.

- We show how to adapt it for parallelization.

- We compare both versions.

The algorithm in question is named batch inverse. Its purpose is to calculate the multiplicative inverse in the field for a batch of numbers.

Sequential algorithm (Montgomery’s trick)

In a naïve approach, one would invert each element in the array. This would mean applying the extended Euclidean algorithm for each element to compute its inverse. However, since field inversion is an expensive operation, we will use something called Montgomery’s trick.

It starts with an array of elements to invert.

$$a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4 \in \mathbb{F}_p$$

It then computes the accumulated products up to each element.

$$\beta_1 = a_1$$ $$\beta_2 = a_1 \times a_2$$ $$\beta_3 = a_1 \times a_2 \times a_3$$ $$\beta_4 = a_1 \times a_2 \times a_3 \times a_4$$

This could be done with as many products as there are elements in the array.

$$\beta_1 = a_1$$ $$\beta_2 = \beta_1 \times a_2$$ $$\beta_3 = \beta_2 \times a_3$$ $$\beta_4 = \beta_3 \times a_4$$

In the next step, we compute the field inversion for the final accumulated product, using the extended Euclidean algorithm.

$$\beta_4^{-1} \leftarrow eea(\beta_4)$$

This will be the only time we use this expensive operation.

Now, we want to calculate the inversion of each element from the inversion of the final accumulated product. The trick uses the previously accumulated products for this, as follows.

$$a_4^{-1} = \beta_4^{-1} \times \beta_3$$

How does that work? Well, we could explain it by imagining the field inversion as a division. This is an intuitive representation only, since there is no such thing as division in $\mathbb{F}_p$.

$$a_4^{-1} = \beta_4^{-1} \times \beta_3$$ $$\approx \frac{1}{a_1 \times a_2 \times a_3 \times a_4} \times a_1 \times a_2 \times a_3$$ $$= \frac{1}{a_4}$$

The inversion of the accumulated product is equal to the product of all the individual inverses. By multiplying it with the elements we don’t want, those inversions are canceled out, and only the element we want remains.

Now it can calculate the inversion of the previous accumulated product.

$$\beta_3^{-1} = \beta_4^{-1} \times a_4$$

The same idea applies.

$$\beta_3^{-1} = \beta_4^{-1} \times a_4$$ $$\approx \frac{1}{a_1 \times a_2 \times a_3 \times a_4} \times a_4$$ $$= \frac{1}{a_1 \times a_2 \times a_3}$$

This idea would now be sequentially repeated for the remaining elements in the array.

| Element | Inversion of the accumulated product | Inversion of the element |

|---|---|---|

| $a_4$ | $\beta_4^{-1} \leftarrow eea(\beta_4)$ | $a_4^{-1} = \beta_4^{-1} \times \beta_3$ |

| $a_3$ | $\beta_3^{-1} = \beta_4^{-1} \times a_4$ | $a_3^{-1} = \beta_3^{-1} \times \beta_2$ |

| $a_2$ | $\beta_2^{-1} = \beta_3^{-1} \times a_3$ | $a_2^{-1} = \beta_2^{-1} \times \beta_1$ |

| $a_2$ | $\beta_1^{-1} = \beta_2^{-1} \times a_2$ | $a_1^{-1} = \beta_1^{-1}$ |

Which leaves us with every element’s inversion.

But why have we done all this? Well, for an array with $n$ elements:

- A naïve implementation would need $n$ field inversions.

- Montgomery’s trick needs $3 (n - 1)$ field multiplications and only one field inversion.

- Needs $n - 1$ multiplications to compute the accumulated products.

- Needs one field inversion for the final accumulated product.

- Needs $2 (n - 1)$ multiplications to invert each element.

Knowing how expensive the extended Euclidean algorithm is, we will gladly take the trade.

However, this algorithm cannot be parallelized as is. Calculating each accumulated product needs the previous one. Even calculating each element inversion needs the previous inverted accumulated product.

So we will adapt the algorithm for its parallelization.

Parallel algorithm (adapted Montgomery’s trick)

It starts with an array of elements to invert.

$$a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4 \in \mathbb{F}_p$$

But we’ll assume the length of the array is a power of two. This is easy to assume since we can always pad the array until it reaches the next power of two, and then discard the padded values in the end.

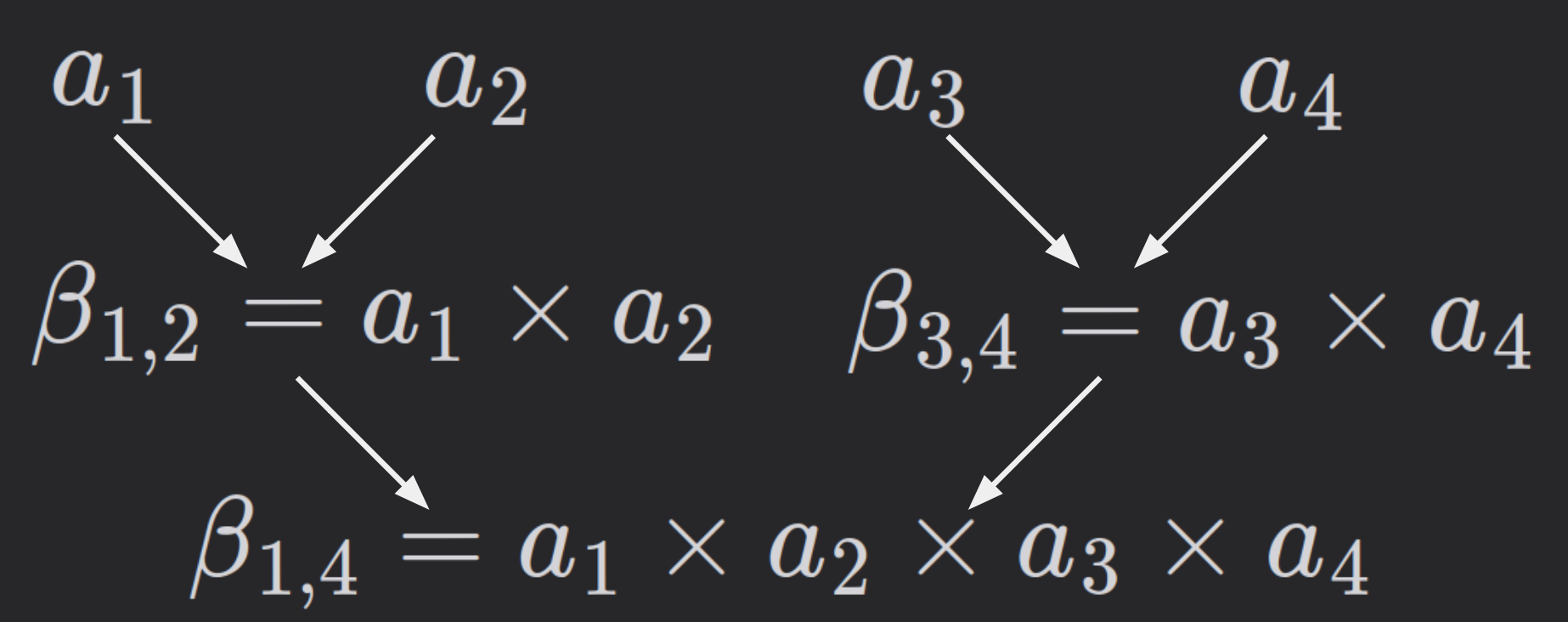

This version of the algorithm computes accumulated products in a binary tree shape.

$$a_1 \space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space a_2 \space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space a_3 \space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space a_4$$

$$\beta_{1,2} = a_1 \times a_2 \space\space\space\space\space\space \beta_{3,4} = a_3 \times a_4$$

$$\beta_{1,4} = \beta_{1,2} \times \beta_{3,4}$$

$$a_1 \space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space a_2 \space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space a_3 \space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space\space a_4$$

$$\beta_{1,2} = a_1 \times a_2 \space\space\space\space\space\space \beta_{3,4} = a_3 \times a_4$$

$$\beta_{1,4} = \beta_{1,2} \times \beta_{3,4}$$

Observe that, in the same level of the tree, all multiplications are independent. Therefore, they can be parallelized.

In the next step, we compute the field inversion for the final accumulated product, using the extended Euclidean algorithm.

$$\beta_{1,4}^{-1} \leftarrow eea(\beta_{1,4})$$

This will be the only time we use this expensive operation.

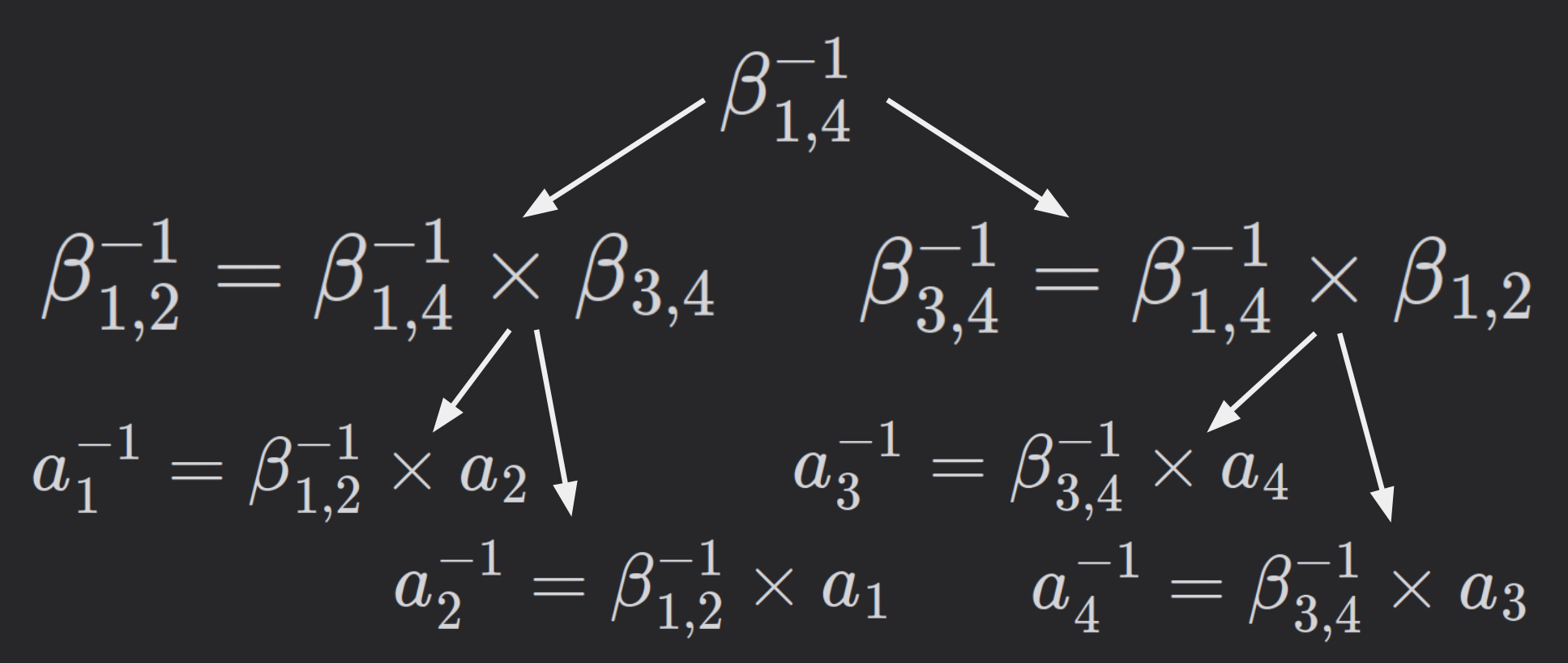

And, just like before, we can use the previous accumulated products to pull apart the components of our inverted accumulated product.

$$\beta_{1,2}^{-1} = \beta_{1,4}^{-1} \times \beta_{3,4}$$

Once again, we apply the same intuition used for the sequential implementation.

$$\beta_{1,2}^{-1} = \beta_{1,4}^{-1} \times \beta_{3,4}$$ $$\approx \frac{1}{a_1 \times a_2 \times a_3 \times a_4} \times a_2 \times a_3$$ $$= \frac{1}{a_1 \times a_2}$$

Then, we continue pulling apart the rest of the products.

$$\beta_{1,4}^{-1} \leftarrow eea(\beta_{1,4})$$

$$\beta_{1,2}^{-1} = \beta_{1,4}^{-1} \times \beta_{3,4} \space\space\space\space\space\space \beta_{3,4}^{-1} = \beta_{1,4}^{-1} \times \beta_{1,2}$$

$$a_1^{-1} = \beta_{1,2}^{-1} \times a_2 \space\space\space\space a_2^{-1} = \beta_{1,2}^{-1} \times a_1 \space\space\space\space a_3^{-1} = \beta_{3,4}^{-1} \times a_4 \space\space\space\space a_4^{-1} = \beta_{3,4}^{-1} \times a_3$$

$$\beta_{1,4}^{-1} \leftarrow eea(\beta_{1,4})$$

$$\beta_{1,2}^{-1} = \beta_{1,4}^{-1} \times \beta_{3,4} \space\space\space\space\space\space \beta_{3,4}^{-1} = \beta_{1,4}^{-1} \times \beta_{1,2}$$

$$a_1^{-1} = \beta_{1,2}^{-1} \times a_2 \space\space\space\space a_2^{-1} = \beta_{1,2}^{-1} \times a_1 \space\space\space\space a_3^{-1} = \beta_{3,4}^{-1} \times a_4 \space\space\space\space a_4^{-1} = \beta_{3,4}^{-1} \times a_3$$

In this tree, it is also true that each operation in the same level can be parallelized.

This leaves us with every element’s inversion.

But how does it compare to the original trick? Well, for an array with $n$ elements:

- Montgomery’s trick needs $3 (n - 1)$ field multiplications and only one field inversion.

- The adapted trick also needs $3 (n - 1)$ field multiplications and only one field inversion.

- Needs $n - 1$ multiplications to compute the accumulated products.

- Needs one field inversion for the final accumulated product.

- Needs $2 (n - 1)$ multiplications to invert each element. So their time complexity is the same.

Performance comparison

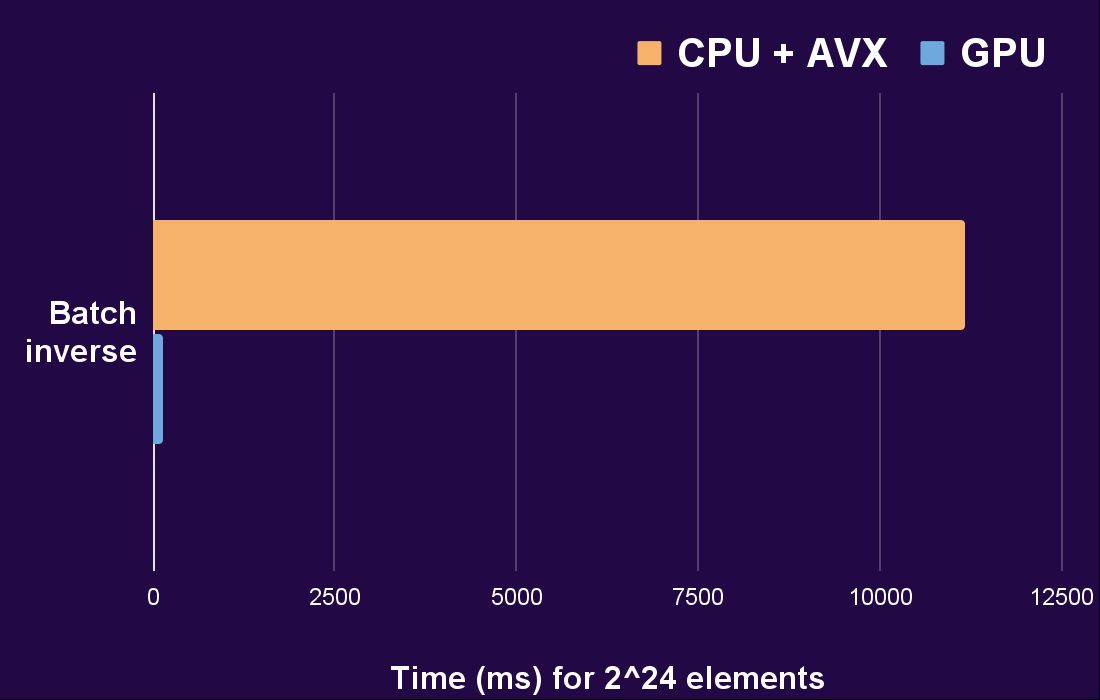

Even while being equal in terms of time complexity, the use of GPU to parallelize the adapted trick clearly makes a difference.

And the difference is ridiculous. Even when comparing against an AVX-optimized CPU algorithm (AVX being a single-instruction-multiple-data architecture).

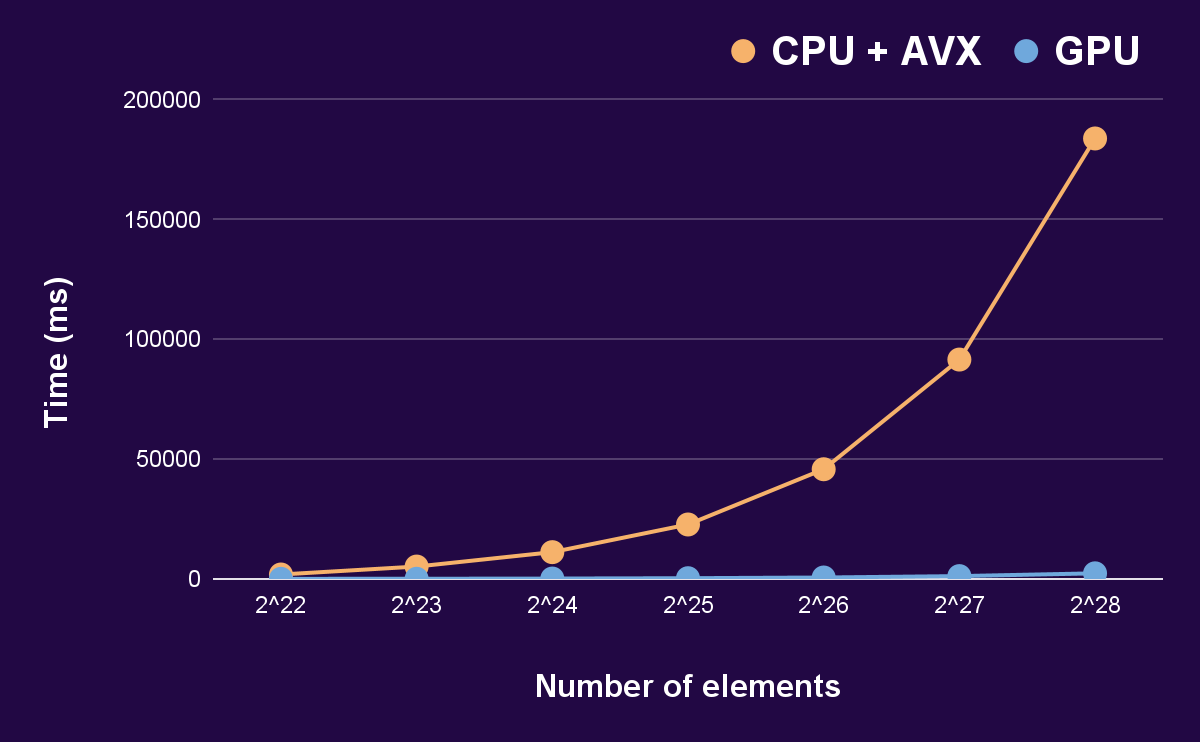

The next chart shows how this difference scales proportionally to the amount of elements involved.

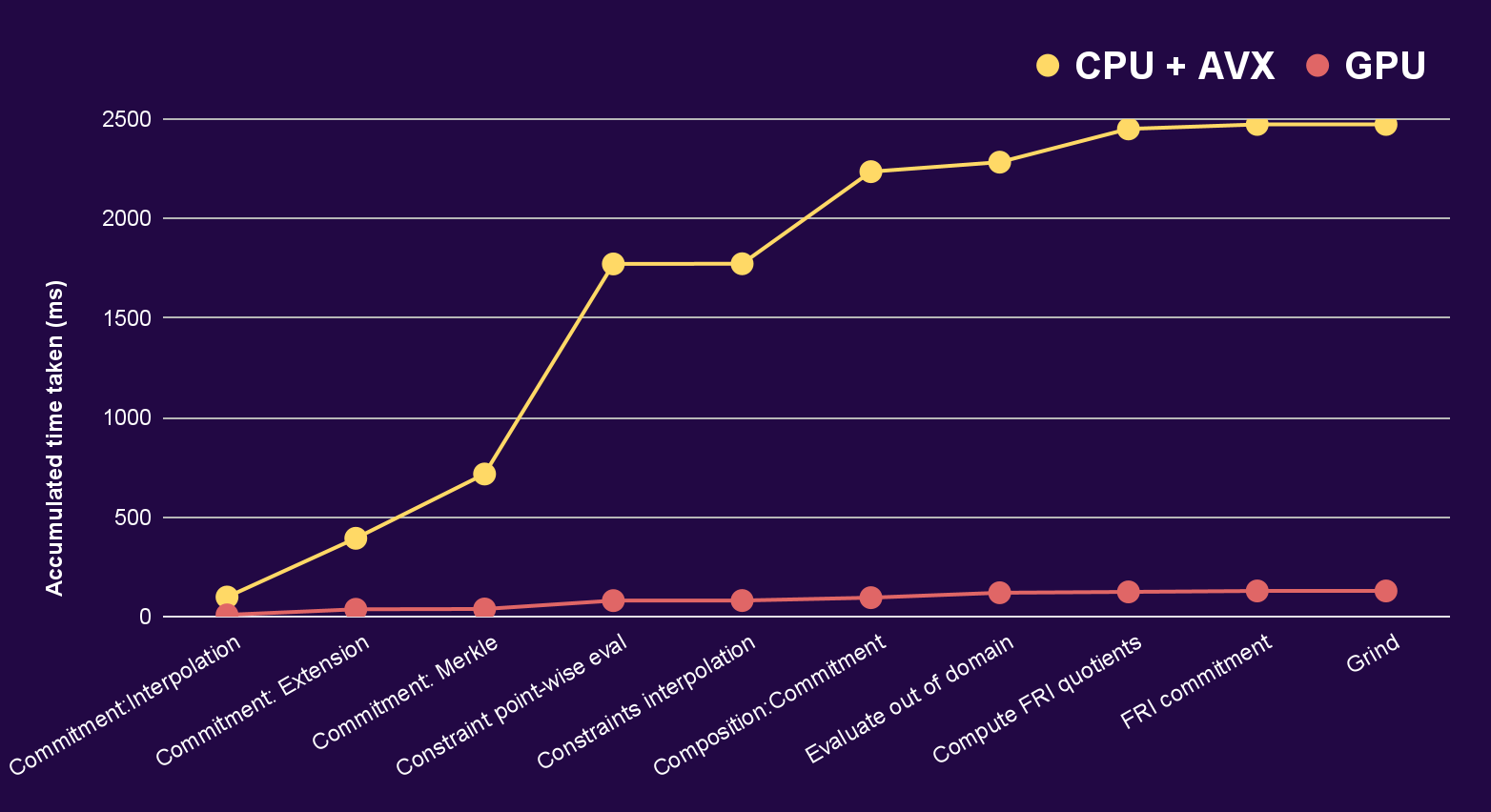

The following graph depicts the time taken for the Stwo prover to compute a proof. Stwo is a Circle STARKs prover self-described as the fastest at the time of writing. The times shown are for the accumulated proving time of CPU with AVX against GPU for the different stages of the proving algorithm.

Once again, the difference is made more than clear. Stwo is made for proving traces of programs. These benchmarks were not run for a real trace, but for a simulated one, using a variant of the Fibonacci sequence.

Conclusions

The main takeaways from all this are the following.

- GPU parallelization is a very powerful tool to make our algorithms quicker and cheaper to run. Harnessing GPU power is nowadays vital for the computation of cryptography primitives.

- A simple heuristic goes a long way in harnessing the power of both high-performance and commodity hardware GPUs. In most cases, a parallelization would consist of implementing a loop with threads. Which would not require any adaptations, like the one shown here.