Introduction

Before I start, I need to say that most of what we did is specific to the Plonky2 proving system, so it won’t be useful when explaining how to do it in general. The idea is to extract abstract concepts and discuss the parts of the process that apply to every (or some) proving system.

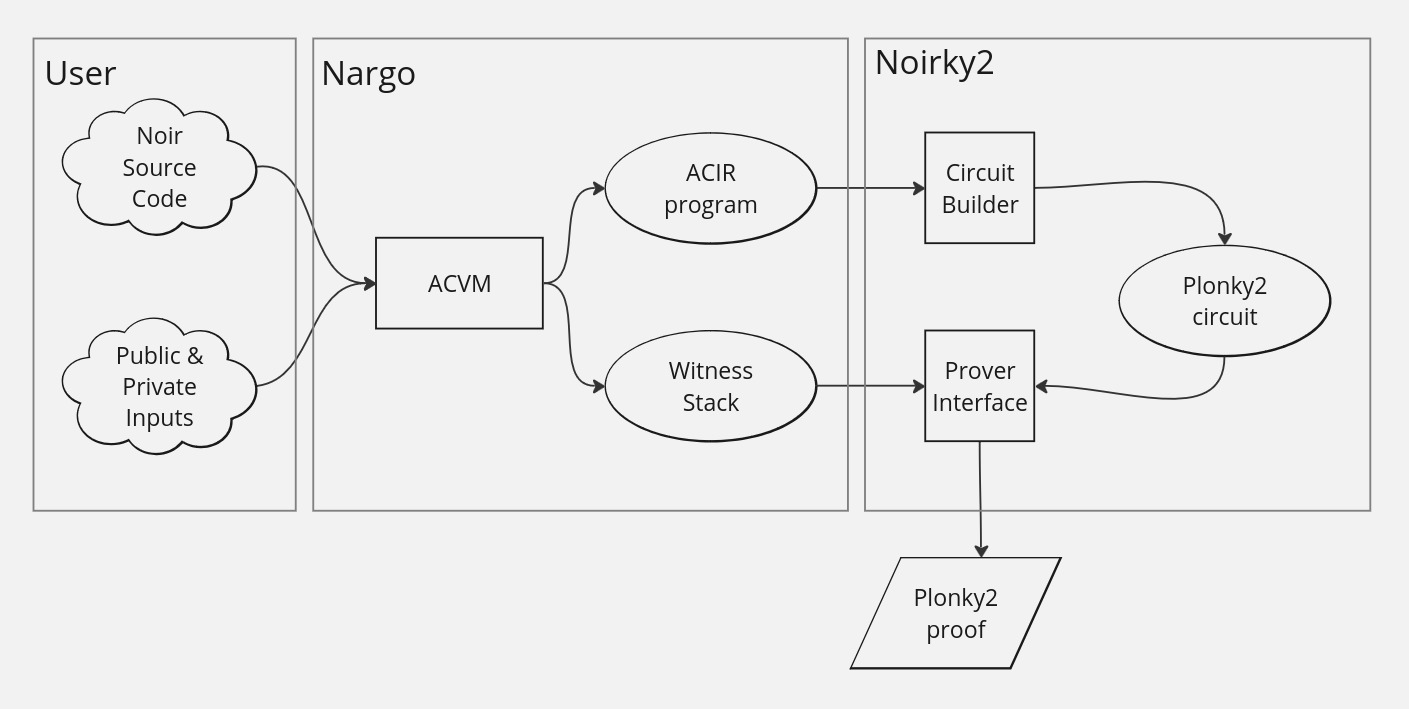

Let’s start by talking about the Noir workflow. In the following image, you can see a simplified representation of the steps taking place from the written Noir program to the generation of the proofs.

The steps are the following (you can check out the map on each step so you don’t lose track):

1) You start by writing a Noir program and, since the idea is to generate a proof of execution with some inputs (private and public) we need to supply input values for the main function (the entry point). 2) When you run the nargo execute command the compiler will do two things:

- Compile your code into ACIR representation and write it in a file.

- Resolve the values of all the variables in the ACIR and write them in a file.

It’s important to note that nargo can generate the ACIR representation of the program before any inputs are provided since the circuit is independent of the execution with concrete inputs.

3) Finally you run the prove command directly from the Noirky2 backend, which will read the mentioned files containing the program and the variables’ values. With that, the backend should:

- Create a Plonky2 circuit.

- Provide that circuit with the generated inputs.

- Generate a Plonky2 proof and write it in a file.

Many things are happening here, so let’s start by talking about the ACIR standard (the ACIR program part of the workflow). ACIR stands for Abstract Circuit Intermediate Representation, and it’s the intermediate set of “instructions” every Noir program compiles to. There are two distinct but similar things: on the one hand, we have the ACIR standard in an abstract sense, the specification of its instructions and how they should be interpreted. On the other hand there’s the ACIR implementation in rust. Luckily for us, Plonky2 is also implemented in Rust, so we took the ACIR implementation from Noir and used it as a dependency in Noirky2. This is not the case for proving systems that are not written in Rust, so deserializing the instructions produced by the Nargo compilation will be the first challenge.

Nargo compiles Noir source code into an ACIR representation which is composed of opcodes. You can think of these opcodes as restrictions over the set of variables, or instructions that conveniently represent our program. For example, think about predicates of the form “x + y should equal 7”. These opcodes are not self-contained because they predicate over variables that Noir calls witnesses. These will be the “variables” of our circuit in this representation, and the one important thing to mention is that they can’t be rewritten: a variable takes only one value throughout its life and that’s it. This comes from the idea that all the mentioned predicates must be mathematically valid at the same time, therefore in ACIR, we don’t have variables like the ones in most programming languages.

The other thing Nargo does is execute the ACIR circuit with the provided inputs. Yes! This happens in such an early stage. This results in a complete assignment of values to the previously mentioned witnesses. Let’s say the opcodes mention witness w~0~, w~1~, w~2~, w~3~ and w~4~, some of which are inputs, and some are intermediate variables of the program. During execution, Nargo resolves the value of each witness (remember the value is static and cannot change) and outputs it. We call this assignment the Witness Stack.

Each of the mentioned products (circuit and witness assignment) is then serialized and saved locally. Why? Well, we said that we wanted to have a decoupled workflow and this is the way Nargo achieves it. Now any proving backend can read the file where the ACIR circuit and the witness values were written, parse them, and build a circuit for its own prover. That’s easy to say, but how difficult it is? To answer that we need to look at what an ACIR Opcode looks like.

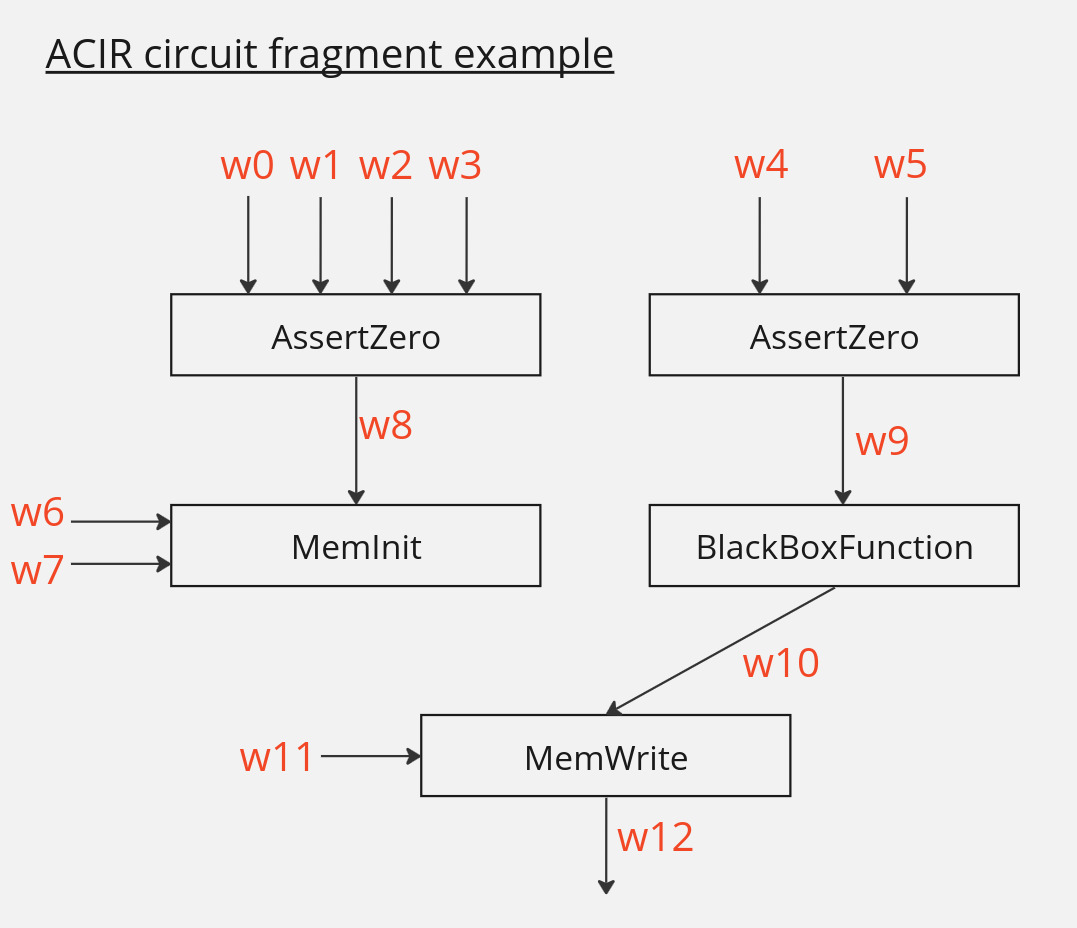

The opcode types are AssertZero, MemoryInit, MemoryOp (read or write), BrilligCall and BlackBoxFunction. That’s it. Well, not quite, there are lots of blackbox functions, but you get the idea.

In an ACIR there’s the concept of Witness. We can think of a Witness as an immutable variable in the circuit. All the opcodes operate over these witnesses which are numbered from 0 to N. Here you can see an example fragment of an ACIR code: the opcodes are presented as boxes. The high-level operations this representation provides, and the witness, are presented as arrows that are inputs and outputs of these boxes.

On the other hand, moving to our example backend, Plonky2 circuits operate over the concept of Targets and Gates. At some level of abstraction these are similar to Witnesses and Opcodes in ACIR, respectively. Throughout the construction of the Plonky2 circuit, we’ll need a mapping between Witnesses and some Targets, more specifically we’ll need an injective function $F: \text{Witness} \rightarrow \text{Target}$. Why? Because two different opcodes can refer to the same witness. In those cases, we’ll want to refer to the same targets while we’re building the circuit. Besides, to generate the Plonky2 proof we need to provide some concrete values to the input targets. The goal here is to build a Plonky2 circuit equivalent to the ACIR provided, while keeping enough information to assign concrete values taken from the Witness Stack to the input targets of the Plonky2 circuit.

To clarify a bit more on the difference between ACIR and the Plonky2 circuit we need to build, here are some important aspects:

- For each different Noir program a different ACIR code is generated, thus a new Plonky2 circuit should be created too.

- The opcodes in ACIR can be somewhat abstract, but Plonky2 (as other proving system implementations) requires a specific circuit created with its API that can be more low-level and require more targets than the number of witnesses the opcode did. That’s why the mapping between Witnesses and Targets is unidirectional (there can be more targets than witnesses, and probably will).

Now, let’s dive into the different opcode types.

Opcodes - AssertZero

AssertZero is the most important opcode and the one you can build most of your programs with. An AssertZero opcode adds the constraint that $P(W) = 0$, where $W=(w_1,..w_n)$ is a tuple of $n$ witnesses, and $P$ is a multi-variate polynomial of total degree at most 2. The coefficients $q_{i,j}, l_i, c$ of the polynomial are known values that define the opcode. A general expression of AssertZero opcode is the following: $\sum_{i,j} q_{i,j}w_iw_j + \sum_i l_iw_i + c = 0$. For example, such an AssertZero opcode is

\[4\cdot w_0 \cdot w_1 + 2 \cdot w_1 \cdot w_2 + 7 \cdot w_0 + 8 \cdot w_5 + 9 = 0.\]At the end of the day this is just saying that the witnesses ($w_i$) should satisfy that equation. A witness can be referenced by more than one opcode since what ACIR models is actually a system of equations with many variables.

Translation to Plonky2

In the backend, translating this opcode is as simple as making use of the ArithmeticGate in Plonky2. Luckily we don’t need to do this directly, since Plonky2 provides a CircuitBuilder object with an API designed to make arithmetic operations between targets in an easy and object-oriented way. We will use operations like:

add(t1: Target, t2: Target)mul(t1: Target, t2: Target)mul_const(t1: Target, c: FieldElement)assert_zero(t: Target)

Other ZK libraries will have its own way of implementing these operations.

Opcodes - Memory Init, Read & Write

Their primary goal is to represent memory read and write operations over slots that are only known at runtime. That means, indexes and values will be given at the time of generating the proof, not when the circuit is built. This means that our circuit must address the fact that any slot of memory can change with a write operation. To say that a slot of memory can change is also a bit confusing since witnesses in ACIR and Targets in Plonky2 are immutable. So, how do we represent memory operations in this context?

Translation to Plonky2

Our solution was to represent each block of memory as an array of Plonky2 targets. Initializing a block of memory with the MemoryInit opcode is equivalent to creating an array of Targets indexed by the block ID the opcode specifies. The opcode has the following information:

- Block ID: used to identify the memory block.

- Witnesses: an array of witnesses that hold the initial values of the memory block’s slots.

The Reading Opcode has the following information:

- Block Id: index of the memory block we’re reading from.

- Index: witness that holds the value of the block index we want to read from.

- Value: witness where the value of the memory read will be stored.

In other words, Value:= SelectedBlock[Index]. To implement this we used the Plonky2 RandomAccessMemory gate through the CircuitBuilder’s random_access() method.

Finally, the Write Opcode has the following information:

- Block Id: the memory block index we’re writing into.

- Index: witness that holds the index we want to write into.

- Value: witness that holds the value we want to write.

You can think of this operation as SelectedBlock[Index]:= Value. Note that Value means very different things in both opcodes. This operation is a bit tricky since Index is not known when building the circuit. During circuit construction we have arrays of targets representing our memory blocks, and these targets have unchangeable values during circuit execution. Therefore, at each write operation we need to create an entirely new array and constrain its values to be the same as the previous ones, except for the position we’re changing. As you can imagine, this operation is rather expensive, but we won’t deep dive into this implementation because it’s too closely coupled with Plonky2. You can check the source code.

Opcodes - Black Box Functions

Black Box Functions are operations just as abstract as Memory Operations. The idea is that in Noir we sometimes want to use some complex algorithm and it can generate a lot of arithmetic restrictions to solve it. Sometimes it can be more efficient to pass the responsibility of building that circuit to the prover backend. This is a subtle application of the XY problem. Instead of ACIR giving its own idea to the backend on how to solve the problem, it just says “Hey, I want to prove I’ve executed this algorithm, can you generate the circuit for it? Here’s the specification.” and then the backend builds the circuit. Some examples are the SHA256 compression function, the ECDSA signature verification, and bitwise operations over different size words (AND & XOR).

A lot can be said about the implementation of bitwise operations in a Plonky2 circuit, but we’ll save those details for another post. The important thing is to understand the philosophy behind blackbox functions and why they’re important.

Opcode - Brillig

Brillig is a kind of opcode that shouldn’t be here. But really, this opcode does not generate any constraint in the circuit, they are rather the result of unconstrained Noir function calls and we should do nothing with them, except assign the hint values to the prover circuit before generating the proof.

Finite field

One of the biggest problems was the finite field Nargo uses to solve the witness values. All operations use the BN254 curve prime, a 254-bit prime number. This is also Barretenberg’s prime. Tha’ts the default proving system of Noir. But Plonky2 uses the Goldilocks prime, a 64-bit prime number \(2^{64} - 2^{32} + 1\) As you can see, the BN254 curve prime doesn’t fit into Goldilocks, it would take 4 Goldilocks field elements to represent a single BN254 field element.

At the time this backend was being implemented, Noir didn’t have a way to select which finite field to use in its calculations, and this was a problem for us since the Witness Stack was full of values and results calculated in a different field. Our solution was to fork the Noir repository and create a different Field Element to be used by Nargo’s ACVM (Abstract Circuit Virtual Machine), that’s also why to use Noirky2 is necessary to use the forked version of Noir (or just, you know, use the dockerized version).

The usage of a different field size has another downside, which is the restriction over the integer size you can use in your Noir programs. Right now, when using Noirky2 you should not exceed the u32 or i32 size. This problem may or may not arise for proving systems other than Plonky2, depending on its field size.

Conclusion

There are many things to consider when building a prover backend for Noir. We scratched the surface in this post but as always the devil is in the details, and there are many details. I hope now you have a general view of what this is all about, but it’s a complex topic and you might need a couple of reads to really understand what’s going on.

External references for deep diving into the topic

ACIR specification in Noir repository